Income invested and remaining in estate

| Surplus income per month | £1,000 |

| Value (if invested) after 10 years* | £155,929 |

| *5% return net of charges, paid monthly in advance | |

| IHT payable on death (where no Nil Rate Band available) |

£62,372 |

Pensions

Last Updated: 6 Apr 24 15 min read

1. Key Points

2. The facts

3. Pension contributions for others

Pension planning and making contributions for others can be an effective way for the donor to reduce their taxable estate while saving into a pension for someone else.

We’ll look at three planning strategies involving pensions and inheritance tax (IHT). And you can find details of pension-specific aspects of inheritance tax in our Inheritance Tax and Pensions Facts article.

Many inheritance tax (IHT) planning strategies involve making significant capital payments. The objective in doing so is to reduce the taxable estate. A trust is often used to retain control over the ultimate destination and timing of benefits.

One option is to use the tax advantages offered by contributions to registered pension schemes for 'others'.

People mistakenly believe that you will be limited to a contribution of up to £3,600 gross for your children or grandchildren. When the initial reply is followed up by the supplementary question; 'what if that child is in employment and earning £50,000 per year?' the size of the opportunity becomes apparent.

The benefits:

The contribution will be treated as having been made by the scheme member for income tax purposes so will operate as described in our Tax Relief on Member's Contributions article.

Devolved Taxation

Scottish taxpayers will pay the Scottish rate of income tax (SRIT) on non-savings and non-dividend (NSND) income. NSND income includes employment income, profits from self-employment (including sole trades and partnerships), rental profits, and pension income (including the state pension). Similarly, from 6 April 2019 Welsh Taxpayers pay the Welsh Rate of Income Tax (CRIT (C for Cymru)) on NSND income.

Other tax and deductions such as Corporation Tax, dividends, savings income and National Insurance Contributions etc. will remain based on UK rules. This could mean the amount of income tax relief which can be claimed on pension contributions by Scottish and UK tax payers may not be the same. For more info on SRIT and how this works in practice, please visit our facts page. For more info on CRIT and how this works in practice, please visit our facts page.

The IHT treatment will depend on whether the transfer of value (the contribution), is exempt or potentially exempt as described in the IHT articles.

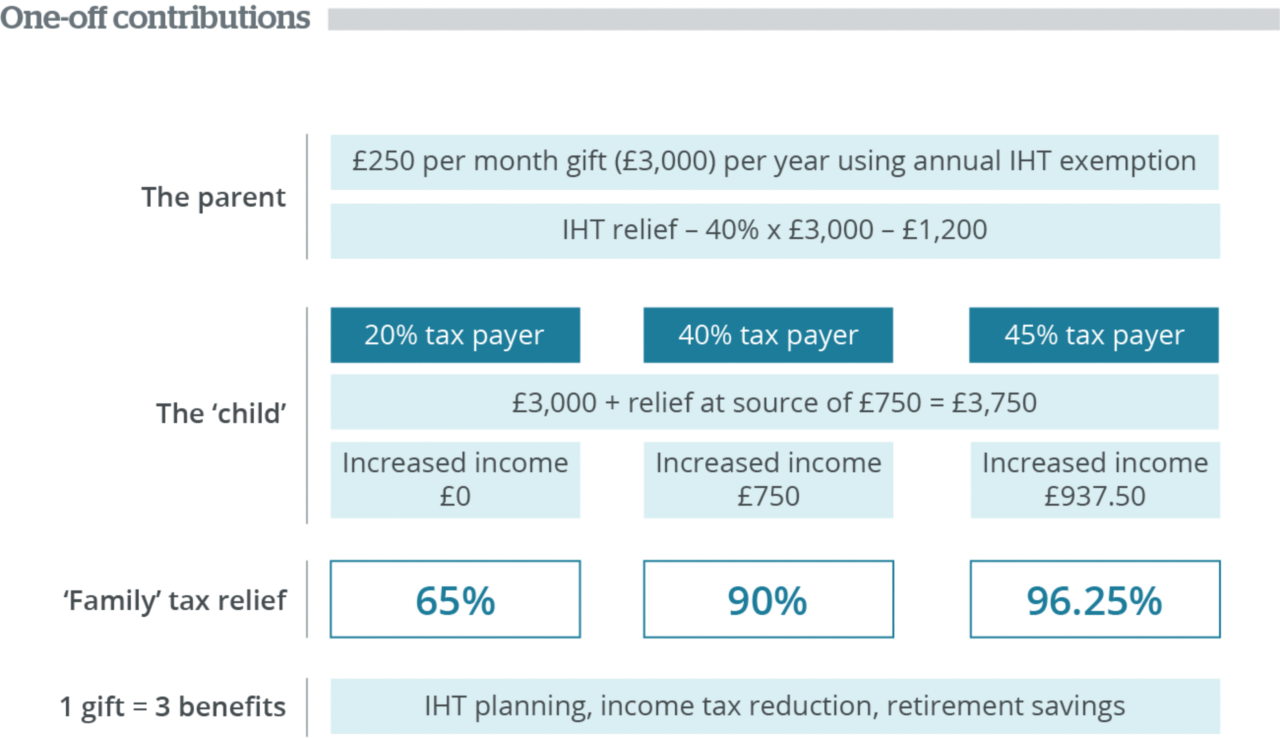

A one-off exempt gift can satisfy multiple planning needs and pass money down the generations tax-efficiently.

The same principles would apply to larger gifts using potentially exempt transfers but death within seven years could reduce or negate the IHT benefits.

Regular contributions can be made using the £3,000 annual exemption available.

Larger regular gifts could be made out of surplus income using the 'normal expenditure out of income exemption'.

| Surplus income per month | £1,000 |

| Value (if invested) after 10 years* | £155,929 |

| *5% return net of charges, paid monthly in advance | |

| IHT payable on death (where no Nil Rate Band available) |

£62,372 |

The 'Child's' Position |

Basic Rate Tax Payer |

Higher Rate Taxpayer |

Additional Rate Taxpayer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accumulated pension fund | £194,912 | £194,912 | £194,912 |

| Increase in income per annum through tax relief | £0 | £3,000 | £3,750 |

So:

This strategy can also be used if the child is caught in a tax trap, such at the High Income Child Benefit Charge, which can be read in this article.

Contributions to your own pension scheme are not usually lifetime transfers of value. If the contributions are made while the member is in good health there will be no transfer of value. But if made while the member is in ill health, there may be a transfer of value.

If we assume that there is no transfer of value then there can be a benefit to making pension contributions to your own pension for others to benefit from and save IHT. But the question as to whether or not this would make your beneficiaries richer depends on many variables;

To illustrate the point, let’s assume that we are looking at a higher rate taxpayer (40%), who has no lump sum and death benefit allowance (LSDBA) and has an IHT issue. They have £10,000 that they are looking to use for IHT planning purposes.

If that £10,000 stays in the estate, after IHT the beneficiaries will get £6,000.

If that £10,000 was paid into a relief at source defined contribution scheme, this will be grossed up to £12,500. However, once a tax return has been completed the amount of the contribution means that they get back £2,500 in their tax return as they had paid sufficient higher rate tax to justify this.

So to get £12,500 in a pension has cost them £7,500. This saves £3,000 in IHT.

If taken as a lump sum by a beneficiary, this would be subject to income tax at their marginal rate as the deceased member had no LSDBA available. If the beneficiary was subject to additional rate tax they would get £6,875 (£12,500 less 45% tax). So on the face of this the beneficiary is £875 better off taking this as a lump sum (perhaps the scheme rules only allow a lump sum).

But we have to remember that there is still £2,500 that came back in the tax return based on the original £10,000 pension contribution. The net cost was £7,500, so there is £2,500 still in the estate. After IHT that would provide an additional £1,500. So the net benefit to the beneficiary is £8,375. So by definition in this example the beneficiary is £2,375 richer assuming no growth.

The above is basic example. A beneficiary with a lower marginal rate of tax would net more (assuming there's no child benefit or personal allowance tax traps at play). Furthermore, we have also assumed there is no LSDBA available. If there is LSDBA available the beneficiary would net a higher amount.

This is where more variables come into play, as we also have to factor in the income tax position of the beneficiaries as well as when the member dies.

Keeping the above example, if the benefits from the pension are taken as a lump sum by a beneficiary subject to additional rate tax the net benefit (including the £2,500 left in the estate) would be £8,375.

But if the beneficiary can take this as an income using beneficiary drawdown or annuity which is set up within the 2 year window of the scheme becoming aware of the members death, then the drawdown/annuity income will be paid tax free. See Death benefits from defined contribution schemes for more information on this.

Add on the £1,500 received from the estate after IHT has been paid as before and that £10,000 that was subject to IHT has become £14,000 (£12,500 tax free income plus £1,500).

The benefits will be taxable at marginal rates for a beneficiary (assuming the beneficiary is a person and not a trust for example). Now we have to factor in what that would be, and we are assuming that the death benefit is taken wholly within that tax band.

If the beneficiary is a basic rate taxpayer, then they would net £10,000 from the pension and £1,500 from the estate. A net £11,5000 from the original £10,000 that was being used for planning. A higher rate beneficiary would get £9,000 all in, and an additional rate taxpayer would get £8,375.

If we compare what the beneficiary would get if that £10,000 was left in the estate, a basic, higher rate and additional rate beneficiary would be better off with the member putting this in the pension than simply receiving £6,000 from the estate after IHT.

All of the above have of course been run on various assumptions and for each case this would be client specific, but while the results may vary, the calculations don’t. After speaking to your client, checking what they want to happen, what the beneficiaries tax rate would be, what the scheme offers and of course that the contributions themselves are going to be exempt from IHT then the numbers won’t lie as to what would make the beneficiaries richer.

Registered pension schemes do not enjoy a general exemption from IHT. However, there are specific provisions which grant relief in many situations.

The treatment of pensions for IHT purposes is covered in our article Inheritance tax and pensions.

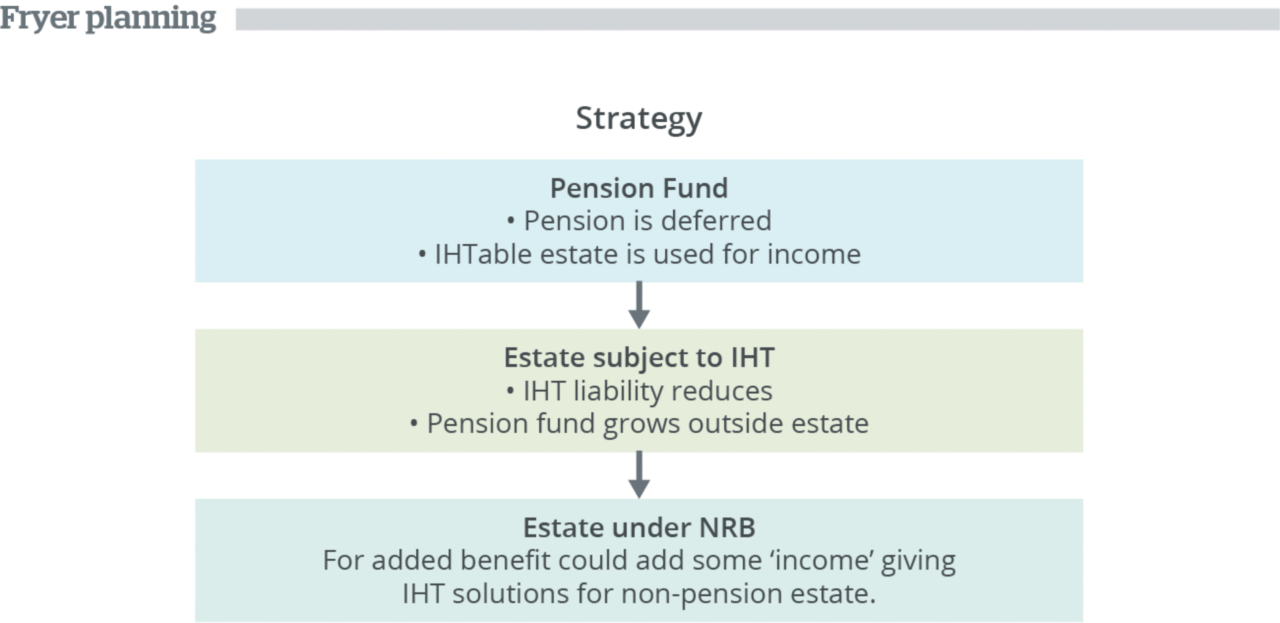

Given the beneficial IHT treatment of pensions a logical approach to IHT planning could be to finance all living expenses from non-pension assets, at least until age 75. These assets are 'in the estate' so using them up would potentially lessen any future IHT bill.

Inheritance Tax 1984 section 3 (3), which was designed to prevent the diminishing of an estate by deliberately failing to exercise an option, was a significant drawback for this strategy. However, this legislation was removed for pensions in Finance Act 2011. This means it is possible to:

The repeal of section 3(3) in relation to pension funds has widened the spectrum of potential planning strategies.

Submit your details and your question and one of your Account Managers will be in touch.